It’s interest rate projection season here at GOBankingRates. While consumers are busy preparing for the holidays and end-of-year celebrations, we’ve been hard at work analyzing interest rate trends from 2014 and making predictions for what 2015 will bring. Let’s take a look at what rates have been doing over the last year, where they are expected to land in 2015 and what it all means for consumers.

It’s interest rate projection season here at GOBankingRates. While consumers are busy preparing for the holidays and end-of-year celebrations, we’ve been hard at work analyzing interest rate trends from 2014 and making predictions for what 2015 will bring. Let’s take a look at what rates have been doing over the last year, where they are expected to land in 2015 and what it all means for consumers.

Interest Rates 101

Before we get started, let’s have a quick lesson on what actually causes interest rates to go down or up: what the Fed does, what inflation is, how rate cuts and increases affect inflation, and the difference between target and prime rates.

The Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (also known as the Federal Reserve or just the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. The current Chair of the Federal Reserve is Janet Yellen, who was appointed by President Barack Obama in February 2014.

The Fed’s three key objectives for monetary policy in the United States are:

• Maximum employment

• Stable prices

• Moderate long-term interest rates.

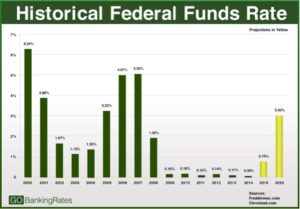

One way it attempts to achieve this is by controlling the federal funds rate — the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans, which impacts interest rates.

Inflation

On its most basic level, inflation is the rate at which the prices of goods and services rise. As inflation rises, purchase power falls — every dollar buys a smaller percentage of that good or service. The Fed tries to sustain a rate of inflation of 2 to 3 percent to keep the growth of prices at a minimum.

There is no universal agreed-upon cause of inflation, but there are two widely accepted theories: demand-pull and cost-push. Demand-pull is essentially “too much money chasing too few goods” and cost-push is basically “too many people chasing a single good or service.” The oil crisis of the 1970s is a good example of cost-push inflation — the cost of gas dramatically increased and consumers had no suitable alternative.

Both theories actually describe overall aspects of inflations: demand-pull explains how it starts and cost-push describes why it’s so difficult to control once it starts.

Related: 10 Best Bank Accounts to Beat Inflation

Interest Rate Cuts

When the federal funds target rate is reduced, interest rates get cut. The Fed rate is important because many other rates follow this rate closely. Fed rate changes help the economy strike a balance between low inflation and sustainable economic growth; when rates are low, there is more money available for lending, which trickles down to consumers and stimulates economic growth.

Low rates are great for consumers in the market for a new house or car — they encourage borrowing. If rates are too low, they can cause excessive growth, which can lead to inflation. Inflation erodes purchasing power and can lead to unsustainable economic expansion.

Low rates also aren’t good for savers; consumers yield next to nothing on short-term CDs, money market accounts, and checking and savings accounts.

Interest Rate Increases

The Fed raises the federal funds target rate to slow inflation and return economic growth to sustainable rates. Rate increases impact consumers’ wallets, depending on how dramatic the increase is. Higher rates mean it’s more expensive to finance goods, like homes or cars, or pay off debt.

Rate increases can also have a negative impact on people who live off a fixed income: Increased inflation affects their standard of living, since they don’t have the ability to increase their income. If rates get too high, financing is too expensive, which slows the economy and can even lead to contraction — a decline in growth for two or more consecutive quarters.

Interest rate increases aren’t necessarily always terrible news for consumers — they are meant to stabilize growth, avoid hyperinflation and can also be a sign the economy is improving. Rate increases are also favorable for consumers with liquid assets — short-term CD, money market, checking and savings accounts will yield higher returns.

Target Rate vs. Prime Rate

The Fed’s target rate is for bank-to-bank lending. The prime rate is the base rate banks charge consumers. The most credit-worthy consumers can get prime rate financing, the lowest possible rate available; but the more credit risk a consumer poses, the higher his rate will be over the prime rate. That’s what lenders call “prime plus premium” — your premium is affected by your credit score, assets, income and more.

Current Interest Rates: A Brief History

In 2007 to 2008, the Federal Reserve took extreme actions in response to the financial crisis in order to stabilize the U.S. economy: Short-term interest rates were reduced to near zero to help households and businesses finance new spending and stabilize prices. Since then, interest rates have stayed low and the economy has showed slow signs of improvement.

Early 2014

The majority of economists didn’t expect a rate increase in 2014, and they were right. Early 2014 saw the same low rates we have today, but there was a surge in the housing market and new car sales.

From a historical standpoint, car loans were at bargain-basement prices and terms were incredibly competitive between both big banks and credit unions. International Business Times reported that 2014 new car sales were on pace to hit their highest rate since 2007, immediately before the Great Recession.

Home buyers continued to take advantage of still-affordable home prices and the historically low mortgage rates they saw at the end of 2013. At the turn of the year, home prices were 31.5 percent below their 2006 peak and the percentage of monthly family income spent on mortgage payments was just 15.6 percent, down from 23.5 percent in mid-2006, according to data from Clear Capital.

Mid-2014

In the summer of 2014, Fed officials predicted the target interest rate would be 1.13% at the end of 2015 and 2.5% a year later, which was higher than previously expected. In March, they estimated the rate would rise to 1% by the end of next year and 2.25% at the end of 2016. Yellen downplayed the significance of the rate forecasts, saying, “I think every participant who’s filling out that questionnaire has a considerable band of uncertainty around their own individual forecast.”

Late 2014

The end of 2014 saw some surprising U.S. economic data: The Labor Department’s October jobs reports showed unemployment was down to 5.8 percent (its lowest level since 2008) and the economy added 214,000 jobs. At the same time, average U.S. gas prices fell below $3 a gallon for the first time since 2010, according to AAA, and the U.S. dollar touched a four-year high of 88.19, reports Reuters.

Still, retail sales growth was slow and new housing construction fell in October. The Fed lowered growth expectations for the remainder of 2014 and kept the short-term interest rate near zero. New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley said in an October speech, “It is still premature to begin to raise rates. The labor market still has too much slack and the inflation rate is too low… The consensus is that lift-off will take place around the middle of next year. That seems like a reasonable view to me.”

2015 Interest Rate Predictions

Late in 2014, the Fed indicated that mid-2015 will see a rate increase, but there is no definitive word on how much or exactly when. When asked, Yellen only said the Fed expects rates to stay low for a “considerable time,” but declined to say just how long. She has repeatedly stated it all depends on how the economy performs. Interest rate forecasts are based on some of the most difficult economic variables to predict, but that hasn’t stopped experts from trying: Most private economists agree that the Fed will raise rates mid-2015, but investors are betting on rates staying at record lows for longer, according to Bloomberg.

But at a June press conference, Yellen warned investors not to become overly confident in the current monetary policy. It is important “for market participants to recognize that there is uncertainty about what the path of interest rates, short-term rates, will be, and that’s necessary because there’s uncertainty about what the path of the economy will be,” she said. “Economic activity is rebounding in the current quarter and will continue to expand at a moderate pace thereafter.”

What does this all mean? The Fed has confirmed a rate hike will happen, Janet Yellen has warned investors not to get too comfortable and the economy is actively rebounding, but the timing is still unclear and experts continue to debate the issue. Whether we see a rate hike in the first quarter or third, here is what consumers can expect sometime in 2015:

Mortgage Rates

The housing market of 2014 was better than it had been in years, with a low number of homes entering foreclosure, favorable mortgage rates and more affordable housing options available to consumers. The impact of a mortgage rate hike really depends on the kind of financing the consumer has, whether the mortgage has a fixed or adjustable rate, and what the loan is tied to.

The housing market of 2014 was better than it had been in years, with a low number of homes entering foreclosure, favorable mortgage rates and more affordable housing options available to consumers. The impact of a mortgage rate hike really depends on the kind of financing the consumer has, whether the mortgage has a fixed or adjustable rate, and what the loan is tied to.

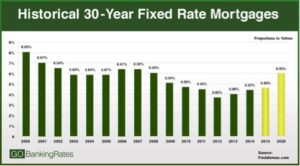

30-year fixed-rate mortgages are typically tied to the yield on 10-year treasury bonds, and rates on adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) are tied to the federal funds rate. The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate fluctuated between 4% and 4.5% for most of the year, and Freddie Mac is predicting rates will rise to 5% in late 2015.

Here is an estimate of how a rate hike might impact a monthly payment on a 30-year, $200,000 mortgage:

• Current rate: 4.22% = $980 per month

• 2015 rate: 4.40% = $1,002 per month

• 2020 rate: 6% = $1,199 per month

In 2015, median home prices, mortgage rates and number of homes for sale are expected to see a moderate increase. Remember: Increased rates aren’t always bad for consumers. They are meant to stabilize growth to a sustainable pace. Higher mortgage rates, stabilized pricing and an increase in inventory will hopefully help solve the supply and demand issues that plagued 2014.

Credit Card Rates

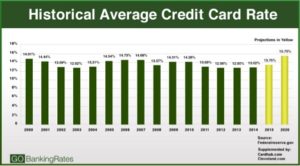

Consumers with fixed-rate credit cards won’t see a change in their payments, but those with variable rate cards will. Most credit cards are linked to the prime rate and a federal funds rate increase will lead to higher interest payments. The average consumer household with credit card debt carries a whopping $16,000 balance, according to NerdWallet, and they should expect a change in the payment and terms.

Consumers with fixed-rate credit cards won’t see a change in their payments, but those with variable rate cards will. Most credit cards are linked to the prime rate and a federal funds rate increase will lead to higher interest payments. The average consumer household with credit card debt carries a whopping $16,000 balance, according to NerdWallet, and they should expect a change in the payment and terms.

Here is how a rate hike will affect the monthly payments on $16,000 of credit card debt if the borrower attempts to repay the loan within five years:

• Current rate: 13.02% = $364 a month

• 2015 rate: 13.75% = $370 a month

• 2020 rate: 15.75% = $387 a month

Even if a consumer has a fixed-rate card, the credit card company can increase the rate at any time, as long as it provides the consumer with advance notice. Consumers with credit card debt should prepare for a rate increase by either paying off the debt before mid-2015, transferring the debt to a less expensive alternative or trying to negotiate better terms with their credit issuers.

Auto Loan Rates

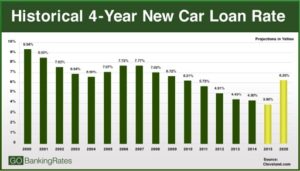

Auto loan rates have been historically low in recent years, leading to an influx of new car purchases in 2014. The National Automobile Dealers Association expects the auto loan rate hike in 2015 to be minimal, with consumers continuing to benefit from favorable lending terms. The rate gaps between new and used cars will narrow, but consumers will still see a large disparity between new and used car loans with four-year repayment terms.

Auto loan rates have been historically low in recent years, leading to an influx of new car purchases in 2014. The National Automobile Dealers Association expects the auto loan rate hike in 2015 to be minimal, with consumers continuing to benefit from favorable lending terms. The rate gaps between new and used cars will narrow, but consumers will still see a large disparity between new and used car loans with four-year repayment terms.

In 2015, auto loan rates will stay low and demand will remain high, which means competition between lenders will be fierce. A recent survey from WalletHub found that credit unions provide 40 percent lower interest rates for new car loans and 44 percent lower rates for used car loans than traditional banks. Car buyers will see better pricing and longer terms from big banks, as they start to vie for a bigger piece of the auto loan pie.

Savings, Money Market and CD Rates

Let’s just call these 2014 rates what they were: brutal. The five-year CD had an increase of 0.04% APY, with all other terms showing zero or even a -0.01% change. As expected, five-year terms also yielded the highest returns, at 1.08% APY, while six-month terms offered just 0.18% APY.

Let’s just call these 2014 rates what they were: brutal. The five-year CD had an increase of 0.04% APY, with all other terms showing zero or even a -0.01% change. As expected, five-year terms also yielded the highest returns, at 1.08% APY, while six-month terms offered just 0.18% APY.

Savings and money market accounts saw the same dismal yields as CDs, with virtually no change from 2013 to 2014, though of the two, money markets had a higher average rate of 0.17% APY, compared to a 0.09% APY average savings account rate.

In 2015, CD fans might find themselves stuck with underperforming investments: Either the rates won’t be competitive in the current market or the rate of inflation will be higher than the yield, and the investment will lose money. Account holders may choose to break the terms of the CD to get into a better rate, which will result in penalties, or they can try to ride out the terms.

Moving forward to 2015 and beyond, it would be wise for consumers to investigate more flexible options, like add-on or bump-up CDs, and split CD investments among varying maturity terms (called “CD laddering“). Traditional banks, credit unions and alternative financial institutions will all offer competitive pricing on savings, money market and CD accounts, so savers should shop around before committing.

The Bottom Line

The Fed will tighten money policy in 2015 before the unemployment rate gets too low, sparking inflation, but it will be a conservative and cautious approach, so as not to disrupt the recovering economy. Interest rates will not begin to rise dramatically until the Fed sees full employment and stable inflation, which probably won’t happen until 2016 or later.